This gets complicated. Ultimately, a discussion about large format photography depends upon whose pleasure we are talking about – the photographer’s or the viewer’s experience with a final image.

With good to great images, the pleasure of the two generally converges.

You could say that the emotion that a final image evokes in the viewer is the deciding factor in everything. Nothing else matters.

Hear me out on this.

People often argue that large format cameras (4 x 5 upwards) are superior to digital because they historically have had a higher resolution than their digital counterparts. That is no longer true. This technical distinction has been based on what is traditionally known as the “resolution argument” and is generally and broadly applied in the discussion of different camera types.

This basic technical resolution argument is now moot. The scientific fact is that the human eye cannot resolve images beyond 64 megs. The standard 4 x 5 large format image is around 64 megabits if you ignore the digital drum scan element which makes that number smaller vs. a traditional paper print of the same format.

That is to say, anything greater than 64 megabits does not materially contribute to a different viewing experience of an image. As with hearing, our sight has physical limitations with regard to resolution, both large and small.

There are many digital cameras that take pictures at 64 megabits.

The other argument traditionally made in favor of the uniqueness of large format photography is that one can compose images with camera tilts, movements, and bellows shifts. Neither is that any longer true because post-production software now allows you to do all that on a computer, albeit with some minor differences.

Image Correction in Adobe Lightroom

In the end, if you make a print of a 64 megabits image from either a large format view camera or its digital counterpart, the observer just can’t tell the difference.

So where is there a distinction?

It’s on the photographer’s side of the world of the camera. And everything before the final print is created and viewed.

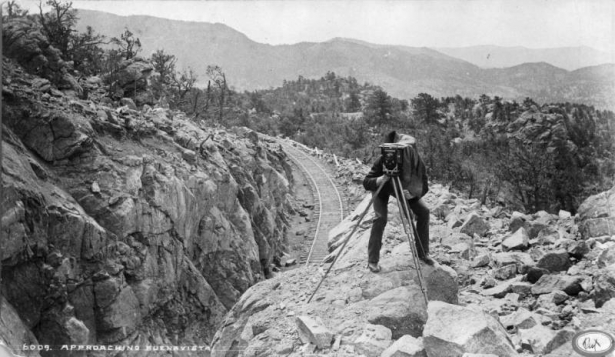

Unlike taking a high-resolution digital image, large format film photography is a more complex physical undertaking involving multiple pieces of glass and equipment, and weight.

The differences between the two couldn’t be more different. One is heavy, one is light. One is slow, one is fast. One has to be dragged around in a huge case, one can be carried anywhere easily in the hand. One requires the assembly of mechanical camera parts for each setup, the other not. One requires multiple settings and an infinite number of choices to be made adjusting engineered metal knobs in rails and slots, the other does not. One requires subjective analog focus decisions while the other one may be left to the camera to make focusing decisions based on automated optics and computer chips.

The same is true for the rendering and printing processes.

For any photographer, selecting a format becomes a self-declaration of intent and what pleases them the most. The argument over the technical superiority of either format is irrelevant. By picking large format, for example, the photographer is making a sentimental statement that they get pleasure out of the multi-layered process they have chosen to experience in making images with now-obsolete technology. It is ultimately a nostalgic decision involving their senses and sensibilities and how they seek to approach experiencing time, intention, and flow in the world.

Large-format photographers often state that they enjoy large format because it “slows them down”, and is what they seek in using the format. An image must be very consciously and slowly composed in large format since so much setting up effort is required. The act of taking a large format image is a multi-step mechanical process

But this notion may be equally applied to digital if a photographer works consciously and deliberately to master the present moment at a slower pace. Most digital landscape and portrait photographers do exactly the same thing as large-format photographers in this regard.

That said, with a digital format, no matter how intentional the act of taking an image may be, a photographer misses out on the many other things a large format film photographer, and all emulsion-based film photographers as well, enjoy.

Namely, the process. These are the things large-format photographers seek when they make images.

Things like:

Developing the film alone in the cave-like dark to almost secretly making an image originally created in the light.

The smell of the sharp acrid perfume of different chemicals mixed in the lab.

The deliberate or accidental decisions made on what contrast graded paper to use for printing.

The shining of the enlarger image onto pure white printing paper and exposing the image based on the photographer’s subjective technical judgment.

Seeing an image slowly and mysteriously emerge beneath the liquid surface in a tray with the surprise it provides as it is pulled out from below.

The sensual touch of wet slippery printing paper in water between your fingers or handling tongs to turn a developing image or the wetness upon your hands.

The drying of hands against cloth and then waiting patiently overtime for the image to progressively dry to become the final image.

One is almost ritual-like, the other not so as much.

With digital photography, none of this experience exists.

The marked differences between the two simply lays in what the photographer most enjoys doing in making the image. Neither is good or bad.

So what is the difference between large format film photography and its digital doppelgänger and other formats?

It comes down to how much pleasure the photographer obtains from their image-making process in either format.

The final image that the viewer sees is simply that invisible result and private choice of how a photographer enjoys working with one type of camera and its associated processes or another. The viewer is not part of that process nor that decision. Moreover, one could possibly argue, they don’t even care.

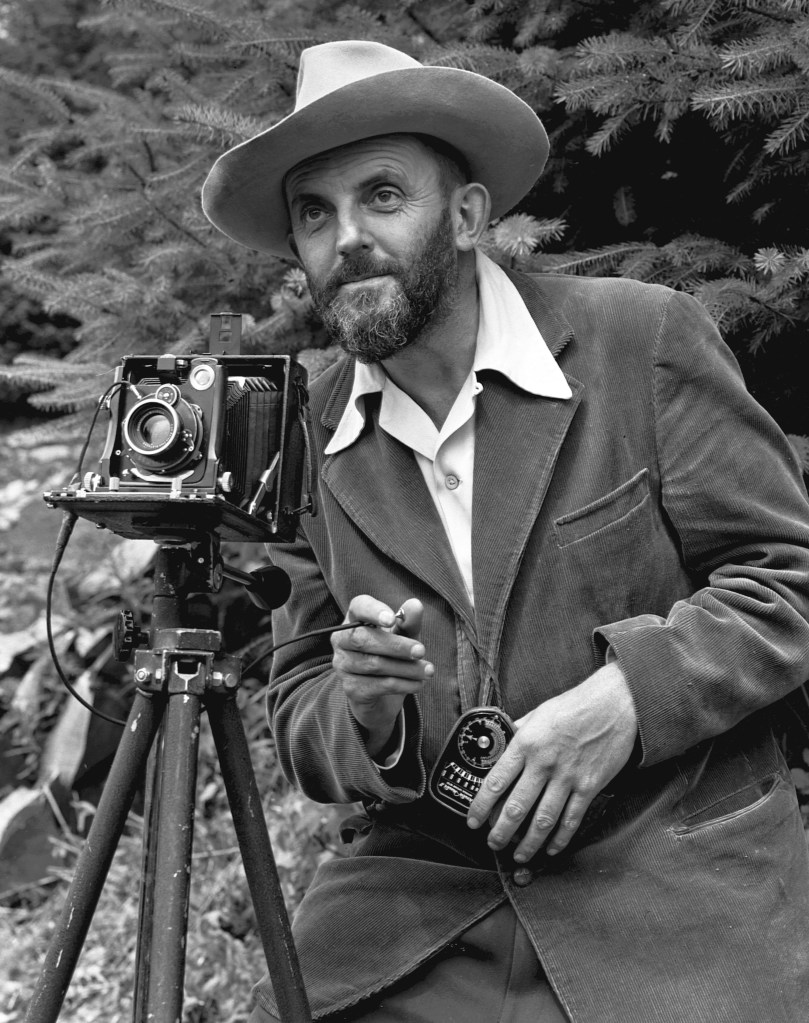

Many large-format photographers, unlike the masters of large format such as Ansel Adams or Joel Meyerowitz, take highly mediocre images but think that using large format makes them good. They hide behind the format because it seems more complicated than other ones. Some call it “more professional” as if the pecuniary rewards obtained through market validation will rub off onto them by using the same equipment type. Others rely on the unspoken tacit assumption that their image should get credit based on the labor expended to obtain the image. Some go so far as to describe the f/stop and shutter speed the image was made with as a part of the image’s title or credit. Others still, even include a description of what kind of paper the image is printed on.

When you see any or all of these things disclosed as part of the image’s context, you know you are looking at a poor image taken by an insecure photographer who knows their work can’t stand up to scrutiny on its own.

In the end, as sad, pathetic, or embarrassing as these well-intentioned pretensions may be, it is a true and good statement about what the photographer takes pleasure in as their photographic process. That confession should count for something to the viewer, even if the image is mediocre or poor. We are being told how, at least, the photographer drew enjoyment in making the image that way.

For the viewer, the final image is everything. In this context, the only thing which matters is whether or not the image triggers an emotion in the viewer. If it does, it is a true thing and should be taken seriously.

For the photographer, the only difference between large format film and others is how the photographer seeks to find pleasure in the making of an image. And that is a true thing and should be taken seriously as well.

Format is irrelevant. Format is everything.

Leave a comment